The first time I encountered Pia Gynell-Jorgensen was, like many first encounters in the Adelaide arts scene, one night in 2023 on the East End, specifically, in Smokelovers, that quaint yet lively cocktail bar on Rundle Street next to the Exeter. Now, it wasn’t the artist I became acquainted with that night - our meeting would come later in the year - but the art itself, in the form of Six Waves, a large and captivating abstract painting commissioned by the bar in early 2023. In this initial encounter, I first observed some of Pia’s distinctive hallmarks: the dazzling grasp of colour fields, the seemingly impromptu mark-making, her characteristically bizarre interpretation of shapes and objects, and, as is often the case when viewing her art, the pursuit of understanding the symbolism between the brushstrokes or recognising the piece’s meaning, if - and it is indeed if - the piece possesses that intangible, difficult to articulate phenomenon of “meaning” that all artists either obsess over or dismiss in absolution.

With a graphic designer for a father and an illustrator for a mother, Pia was born into a household that fostered an environment of creativity and appreciation for the arts. In childhood, she dabbled in performing arts, theatre, and the circus, but felt a natural magnetism towards visual arts as the most serviceable medium to translate her ideas. She now predominantly works with oil paints, graphite, and coloured oil pencils, as well as experimenting with ink, poster design, album art, clothing, and a semi-regular DJ show with Brigitte Kamleh entitled ‘Sink’.

On Tuesday, March 19th, 2024, Pia drove into the city to collect me from North Terrace after my university class. We spent a brief interlude at BWS acquiring some well-earned afternoon beers and soon found ourselves perched quite comfortably in the garden of the beautifully adorned outer-city home she rents with friends of the publication Jay Garland and Char Nitschke. Sipping a Peroni on a wooden deck chair, my initial questions surrounded her creative process, especially when approaching an artistic movement as aesthetically vast and difficult to define as surrealism. How does one take something literal and depict it surrealistically?

“I think, usually, an idea for a piece will come from myself. Not even in terms of making work as an artist, but more so living and understanding with an artist's brain. It'll come from a kind of wacky, unusual understanding of something that's happened in my life, and then I'll think, ‘oh, that's quite poetic. I'm going to try and visualise that.’” - Pia

I then asked her how she navigates between different forms of artistry, and whether they informed one another. With an artistic repertoire that spans various methods and styles, from oil paints to graphite surrealism, she does experience some crossover between techniques, offering the example of creating visual expression from a poetic or text-based catalyst. However, with graphite surrealism and abstract expressionism as her predominant mediums, Pia has found two “excellent languages” to imaginatively speak through.

“I've always been really drawn to surrealist art and books and films. It's a much clearer language than abstraction to depict an idea if you're drawing something literal. I think, in the same way that dreams are a playful way of dissecting our lives, people find something very grounding in indulging in the idea of a warped reality. It gives us another way of understanding what we're all going through, and it's entertaining. It kind of picks up these weird pieces of your life and puts them in a different order and forces you to question what's going on.” - Pia

In discussing surrealism and dreams, we found common ground over our deep admiration for the surrealist American filmmaker David Lynch, who famously refuses to disclose the meaning or lack thereof behind his uniquely strange cinematic experiences. After finishing Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), and many an hour spent reading theories online and formulating various interpretations of it’s perplexing finale, I came across a four-and-a-half-hour-long video on YouTube entitled Twin Peaks ACTUALLY EXPLAINED (No, Really) by a creator called Twin Perfect. Ever the sucker for an extensive video essay, I watched this colossus intermittently over two or three days, admiring this synthesis of research, analysis, and interpretation regarding one of my favourite television shows. However, a lingering dilemma that fluttered in the back of my mind surrounded the conclusive satisfaction of solving the puzzle in conflict with the excitement and intensity of the puzzle left unsolved.

Lynch’s intention is not to be understood - the code need not be cracked. Twin Peaks remains one of my favourite shows despite, or even because of its unsolved, unexplainable nature. Another example that comes to mind is the finale of HBO’s The Sopranos (1999-2007). Many will recall its controversial cliff-hanger ending, kept intentionally ambiguous: the audience left on the edge of their seats, unsatisfied and unfulfilled when the screen cuts to black,

What does it mean when the mystery, or the meaning, behind a particular piece of art is left unsolved, the answer concealed from the viewer? Well, in the cases of Twin Peaks and The Sopranos, it means that our interest remains firmly attached to these cliffhangers, these unexplained endings. The uncertainty persistently reapplies fuel to the fires of our intrigue. Nearly twenty years after the culminating episode of The Sopranos aired, I continue to engage in passionate conversations with friends about the final scene, routinely reconsidering the different implications of the cut-to-black. Similarly, the final moments of Twin Peaks: The Return are more and more perplexing each time I recall them, and online discourse surrounding the meaning behind Lynch and Mark Frost’s opus remains furiously dynamic.

I promise I’ll relate this tirade back to Pia shortly. The point I’m trying to make is: had these shows provided the viewer with a clear, satisfying, and fulfilling resolution, we would most likely terminate our genuine engagement with the art. Interest in the mystery dies as soon as it is solved. That is precisely why Lynch initially refused to continue working on Twin Peaks after studio executives pressured him into revealing Laura Palmer’s killer. The puzzle, upon its completion, remains idle on the table for a few days or weeks to absorb the fleeting admiration of its observers before promptly being disassembled and placed back in the box, back on the shelf. The excitement of piecing together the puzzle is generated by the act, not the final result. Once all questions are answered and every secret revealed, the magic dissipates, leaving us with a finished picture that, while complete, no longer sparks the same level of curiosity or engagement.

Why are we so painfully determined to solve the mystery or have the code cracked for us? Maybe it comes down to the cognitive stimulation provoked by critical thinking, the satisfaction provided by emotional and intellectual fulfilment, the sense of shared understanding we can feel among others, or, perhaps most potent of all, the powerful feeling of control and mastery we can exert over the fearsome, formidable unknown.

But does this mean we need to understand something to truly enjoy it? I think not. To quote from 20th century French existentialist Albert Camus: “If we understood the enigmas of life there would be no need for art.” Pia’s artworks are surreal and abstract, often difficult to decipher, but I feel no frustration in my frequent inability to instantly perceive her imagery “correctly”. In fact, one may find unquantifiable delight in the ambiguity of non-understanding, the act of merely perceiving the art as art, and participating in the age-old philosophy of art for art’s sake: the notion that art should be attempted for the purpose of the actual creation itself and the belief in art - and by that purpose alone - without concern for how it may (or may not) be received. When presented with a piece of art, should we strain ourselves to understand it perfectly, or can we find within ourselves enough pleasure and satisfaction in the act of perceiving the art alone?

“You can appreciate [Twin Peaks] without spending four and a half hours analysing it. It's funny when people ask me about an abstract piece. It's like, they see the piece, and then they want talking, but the piece is doing the talking.” - Pia

I’m not arguing in opposition to analysis and interpretation - these are two undertakings through which I find an abundance of entertainment. I simply refuse to concede that they are essential requirements for creating or perceiving art. I don’t write to be analysed or understood a particular way. Nor do I write because I feel obligated to provide society with practical utility. No, I write because I want to write, because I must write, because writing fulfils my creative desires and my need to express. By the same token, Pia creates art…

“…because it’s what I'm here to do. It's what I want to do.” - Pia

It was not the intention of the above analysis to create any misguided impression that Pia’s art practice lacks meaning. I have instead attempted to offer a personal interpretation of the essentiality versus inessentiality of meaning in art, particularly in the realms of abstract art and surrealism. In visual art, meaning is not an intrinsic phenomenon, but a local understanding, unique to each viewer, formed through an adaptable contemplative and emotional relationship cultivated between the creator, the artwork, and the viewer.

In point of fact, Pia’s works emit strikingly poignant meaningfulness that can be introspective or outwardly observational, brimming with emotional intensity and sensory expression. A typical Gynell-Jorgensen painting will stimulate idiosyncratic reactions from each viewer’s catalogue of personal experiences and impressions of the world, leading to an indeterminable variation of interpretations, definitions, and meanings. For Pia, the preconceived meaning attributed to a particular painting may remain unchanged prior to, throughout, and subsequent to its completion. The audience, however, participates in an evolving sequence of experiential sensations and critical connections. What this suggests, at least by my understanding, is that the meaning of art is not something fixed and unvarying, but a living dialogue that surfaces uniquely in each observer. This means that each encounter with Pia’s work ensures a dynamic interplay between the individual perceptions of the viewer and the intention of the artist, both of which are influenced by cultural context and self-analysis, producing a transformative, ever-evolving observational meditation.

I hope that analysis was meaningful in some way. But, as I said earlier, meaning is not an intrinsic phenomenon: perhaps it was, perhaps it wasn’t - who am I to decide? At the very least, I’ve had the opportunity to explore a subject matter of great individual deliberation, and that act has itself yielded tremendous personal meaning. Nevertheless, it’s time to return our attention to the true subject matter of this article, Pia.

Recalling her contention that the art itself does the talking, Pia still places emphasis on the value of exhibition labels in coexistence with her art pieces, remarking that they “feel like a part of the piece”. She pays closer attention to the meaning attributed to the piece rather than the creative process when writing her labels, and feels “shattered” when viewers don’t utilise the floor sheets when interpreting an exhibition. I asked her if she hoped that viewers would come away with a greater understanding of a painting after reading the label:

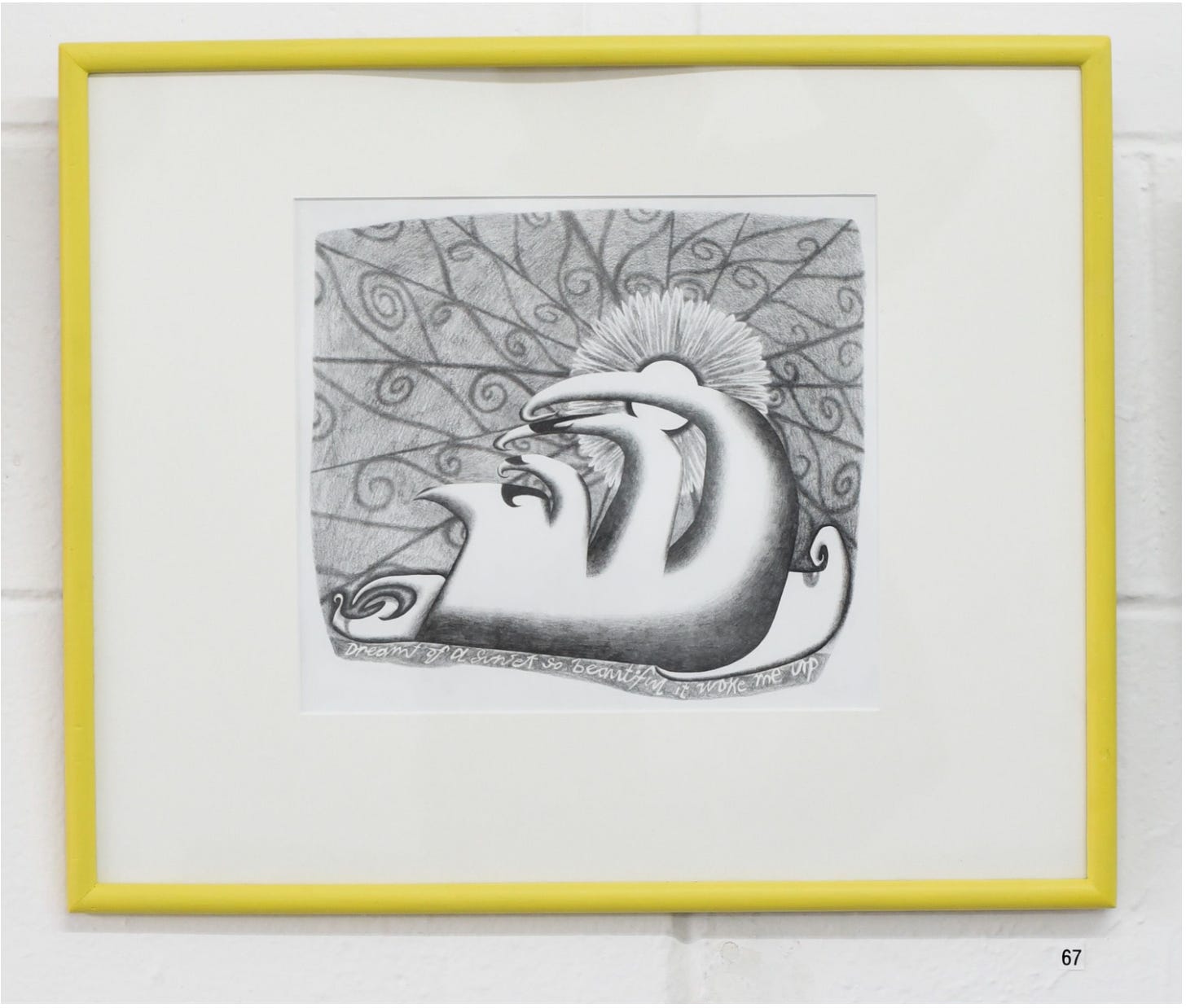

“I guess I'm not doing it for the appeal of giving people a better understanding of it. Often my paintings will be an abstraction of an idea. There's one in my last exhibition called Unley Oval (Viewed From Laying Down) that was a quite literal painting of Unley Oval, with goalposts and houses and hills, but turned on its side. I think people felt a lot of joy in understanding how I got there, which is cool. But it's definitely not necessary. It shouldn't be, I think, in a great piece of art. It's different with different pieces. If it's a piece with a decided message I would like it to be understood in conjunction with the text and received as a whole piece. But some of my paintings are just like fine art scribblings.” - Pia

Another element that plays a fundamental role in her creation is personal introspection and the flow state. She spoke of art’s incredible capacity to “pull you into consciousness, to the point where you'll be in there creating something, looking at yourself, and see the whole world from a mile away”. As a writer, it is remarkably easy to become utterly consumed by the words or the narrative, losing oneself in the act of arranging words onto the notebook or the Word document. In this state of creation, time seems to both slow and accelerate, and the events occurring around you are reduced to insignificance as mind and fingers synthesise in wonderful synchronicity. As a painter, Pia says that it’s an “amazing sensory experience” to put brush to canvas or pencil to paper in the act of transferring ideas from hypothetical theory or impression to authentic material expression.

Perhaps the most personally important aspect of Pia’s practice is play. She believes that the most beautiful pieces of art are those that “contextualise something ugly”, and explained this conviction quite brilliantly through one very long sentence:

“Yeah, what I mean by that is this: by letting yourself completely ruin a composition with certain line work or choosing a colour that's completely off, and in doing something that's not technically encouraged and working with your skills and artistic integrity to make that relevant in a piece, I think that delivers a more mature piece that has more gravitas than if you were to, just from the outset, run towards something that was beautiful rather than let yourself play a little bit.” - Pia

To work this notion into another context, a musician may tell you that there are no wrong notes, and that the organisation of a masterful arrangement of music stems from the use of chords to contextualise the notes. This idea that there are no wrong notes can be traced to the philosophy of musical freedom and creative play. Often embraced in genres that underscore the value of improvisation, such as jazz and post-rock, this perspective offers a resolution or reinterpretation of “incorrect” notes that enhances the music or contributes to its complexity or overall expressiveness. Like an improvisational musician, Pia welcomes imperfections such as “ugliness” into her creative process as organic factors that contribute to the ultimate determination of composition, colour, shape, and texture, creating visual context that defines the significance of each consciously implemented artistic element.

Does Pia feel like art is her purpose?

“That's totally what it feels like. Since I was a kid, I knew what I wanted to do. I think, even then, there was a very serious integrity that I approached drawing with. I took myself very seriously. I still take myself seriously, but I play a lot. I'll accept ideas that maybe other artists won't accept. I'll let myself do things that are technically wrong or don’t look good. I think if you have the artistic integrity to follow through with a playful idea to the point where it becomes fine art, that's when your skills are really on show. It's probably naive, but I have confidence that what I'm doing is valuable to the landscape of art. You know, otherwise I wouldn't be doing it. I'm not doing it for consumption. It feels like there's a massive integrity there when I'm making art.” - Pia

I asked her what she’d be doing with her time if it wasn’t spent creating art. Her answer: music. Having become friends with Pia over the past year, I may have been able to predict this response, considering how integral music has been to her artistic journey. In addition to her DJ performances with Brigitte, she’s collaborated with a number of Adelaide bands, such as Druid Fluids and Pine Point, creating unique pieces for their album covers or gig posters, and says she feels “the pull” of her guitar every single day.

“I get as much out of music as I get from visual art. In another life, I'm a musician who dabbles in visual art. But visual art is where I can contribute, so that's what I do. If I'm a bit snagged on what energy to put into a piece, I'll find myself listening to certain music or certain albums. Because when I listen to these albums, there's a certain aesthetic that comes to mind, and maybe that's me kind of putting myself in a certain emotional state that I feel is most lucrative for making art.” - Pia

Her favourite musicians to listen to when painting include The Beatles, and then, “on the second tier”, everyone else: Frank Zappa, The Lemon Twigs, King Krule, and Midnight Sister to highlight a few. As a music lover, she considers it a natural phenomenon to want to collaborate with musicians. In her view, “music and visual art are a very, very important pairing that humans have found”. She’s discovered a rewarding process in combining aesthetics with musicality and terminology to create visual art for musicians who may not have the exact language to describe the piece they hope for.

In approaching collaboration, Pia is “more often than not using [her] skills to interpret an idea and deliver it with [her] style in the best way possible”, often contriving to fuse styles together and respond effectively to the “push and pull” of dealing with someone else’s concepts or suggestions, which sometimes stray from the desires or intentions Pia approaches her practice with. But, as she says, these clients, or collaborators, have propositioned her specifically.

“So there is something there that they obviously want with my work. And there's always fuel. I've never not wanted to make.” - Pia

It became apparent to me that Pia seems to evade the clutches of creative block. It fills me with envy to recall her admission that she “couldn’t comprehend” how one might feel when facing artistic barriers or a lack of creative drive. As she said, “there’s always fuel”: Pia and her practice never become estranged from one another. Rather, she says she can detect an “almost physical” connection constantly drawing the creator to her craft. For Pia, creating works of art is the “easiest way” she can spend her time, and “never feels like a chore”.

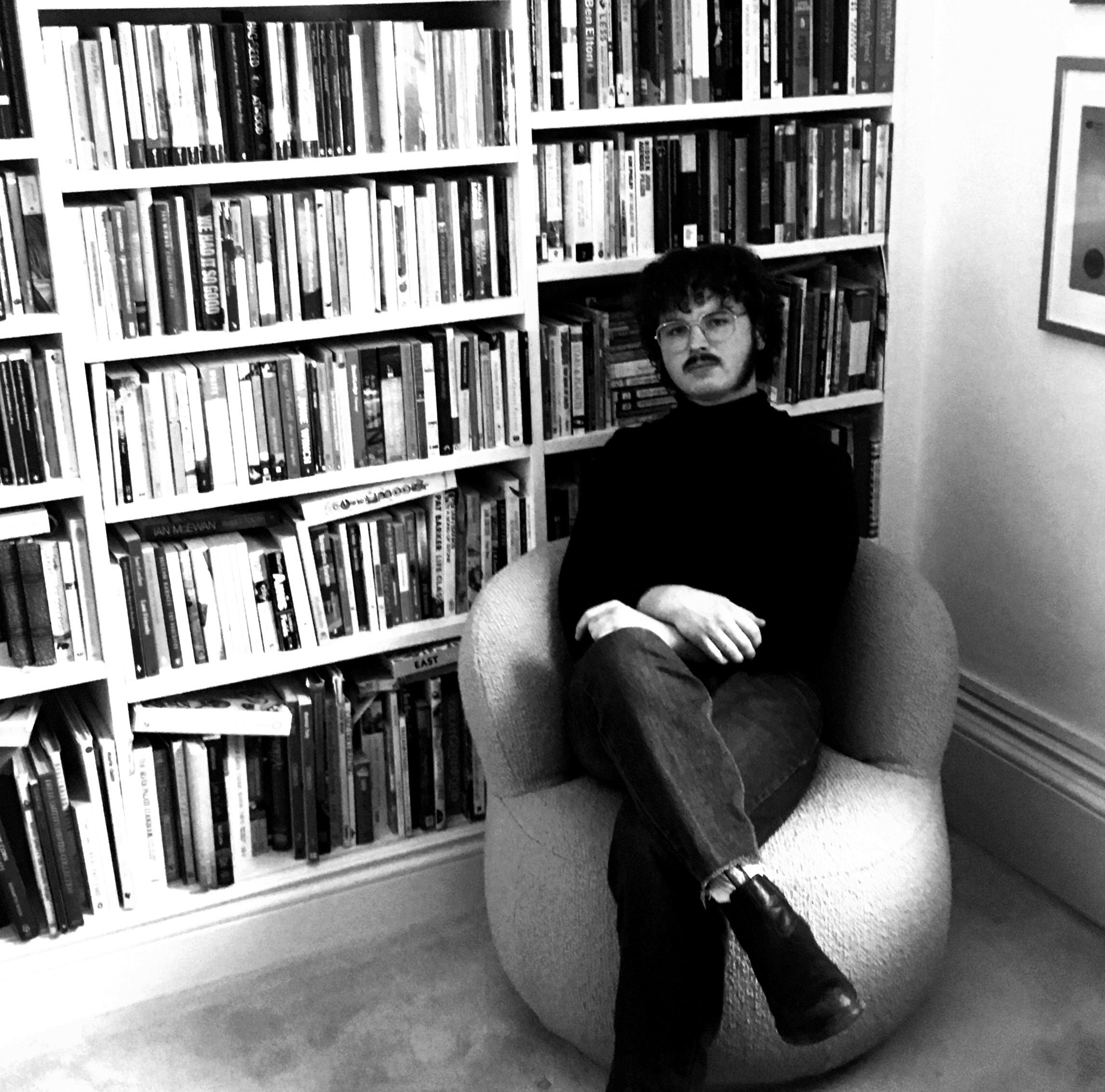

At this point in our conversation it began to rain, so to spare my laptop an untimely demise we scurried back inside, stepping briefly into her home studio for a photo shoot. In this creative headquarters, paints and brushes are strewn across the room in crates or containers, and perhaps a dozen works-in-progress line the walls in varying sizes. Sheets of paper taped to one of the walls feature written lists of her current projects or to-do’s, such as “new work for Billie” and “Dad painting collab”. Next to these lists is a window facing north that allows the room to be flooded with natural lighting on clear days, and during gloomier weather she may call upon the orange, mushroom-shaped lamp next to her record player for additional visibility. Like all artistic spaces, Pia’s studio exudes a sense of organised chaos, a space where creativity can thrive amidst clutter.

After the shoot, we settled down in the living room, where Jay had been practicing sitar when we’d arrived a few hours earlier. Recalling that sight, I realised that Pia and I had spoken at length about her relationship with music but forgotten to discuss her artistic influences. She cites Jean-Michel Basquiat, Joan Miró, Frida Kahlo, and Jack Marshall among others, but, to abstain from becoming “too influenced”, elects to avoid delving too deeply into abstract artists with output similar to her own.

“I still love it. I’d still go to exhibitions and gladly talk about it and view it. But it's maybe not the biggest place of inspiration.” - Pia

For my final question, I asked Pia what advice she had for new or emerging artists seeking their own style or voice:

“Just keep making. If you can afford yourself the time and materials, keep practicing. Creativity kind of fills itself. If the passion's there, you'll move yourself. Marketing yourself is another game. It's often counterintuitive to a lot of creators to sell themselves and present themselves like we need to these days. But I feel like, if the creativity is there, that's the momentum. Just keep, keep making.” - Pia

Pia has already had a highly successful 2024, hosting successful solo exhibitions at Atelier Antifragile on Hutt Street and Backwoods Gallery in Collingwood, Victoria, the latter being her first interstate solo exhibition. She’s had paintings installed in various businesses, designed the cover art for Pine Point’s Be Longing EP, and hopes to begin experimenting with risograph printing, a versatile printing process combining aspects of screen printing and digital photocopying that she admires for its “oldschool”, “grainy”, and “rustic” qualities. She also says she’d like to make a film one day.

Beyond her own work, Pia believes that art shares a position of equal importance with all other forms of media, representing connection, community, historical documentation, educational entertainment, and a tool for the preservation of culture.

“I think you could look at it alongside science, which is arguably our greatest tool for propelling our own evolution. Art is a luxury, sure, but it's a tool. It's almost just as necessary, especially with the kind of global climate right now. It's a luxury. We don't need it to live, but it is extremely necessary for a functioning society. There's a joy that comes from creating and consuming art that is really important. I mean you look at music and how it can bring people together in times of absolute dismay, and I think art, visual art, is the same.” - Pia

Hearing this sentiment of such palpable sincerity reminded me of Robin Williams’ brilliant Seize the Day monologue from Dead Poets Society (1989). I believe it suitable to culminate this article by quoting from that very scene, an example that wonderfully echoes Pia’s reflections regarding the importance of art in our society.

“We don't read and write poetry because it's cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering…these are noble pursuits, and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love; these are what we stay alive for.” - John Keating, portrayed by Robin Williams.

Picture yourself standing in an art gallery whose walls are adorned with the paintings of Pia Gynell-Jorgensen. You’re walking slowly, enjoying the process of perception, taking everything in and applying your individual experiences, impressions, and convictions to each piece, discovering meaning that transforms and alternates in response to internal emotional stimuli. Tomorrow, you have to wake up early and drive to work, or take the tram into town for a university lecture, or perform neurosurgery, or walk your dog, or do the weekly shop for groceries. Whether these prospects are exciting to you or not is irrelevant, because right now, in this very moment, you’re surrounded by spectacular, thoughtful works of visual art. This is what holds your attention, and this is what you’ll remember more than that shift at work or those errands you had to run. You arrive at the centre of the gallery, swivelling around for one last look at the space, gesturing towards everything around you. And finally, while pushing the exit door open and walking out into the street, you think to yourself…

“This is what I stay alive for.”

My thanks go out to Pia for answering my questions and giving me the grand tour of her home studio. It’s a pleasure to interview such terrific local artists practicing on Kaurna Land whilst getting to know them on a deeper level. My thanks also go out to you, friendly reader, if you’ve made it this far. In my efforts to encapsulate the true gravity of Pia’s work, this piece has become perhaps twice the length of my previous articles, so I appreciate your commitment to reading it in full.

But remember, I didn’t really write it for you.

I wrote it for me.

This article was written, recorded, and edited on the traditional lands of the Kaurna People. The Infinite Rise observes that Country is central to the social, cultural and spiritual lives of Aboriginal people. Sovereignty was never ceded. Always was, always will be, Aboriginal Land.