Hell Is An Unskippable Advertisement

Navigating A World of Inescapable Marketing

1. Fifteen Million Merits

Netflix’s speculative sci-fi anthology Black Mirror is celebrated for its harrowing depiction of technology’s rapid evolution in a future plagued by alienation, exploitation, distrust, and socioeconomic unrest. By exaggerating characteristics of contemporary culture, the series analyses the corrosion of humanity’s moral structures as they intersect with increasingly invasive technological systems, such as artificial intelligence, data privacy and surveillance, virtual reality, and robotics.

Black Mirror boasts an impressive catalogue of stand-alone episodes, but presently, I’d like to focus on one in particular: Fifteen Million Merits (2011), starring Jessica Brown Findlay as Abi and Daniel Kaluuya as Bing. Set in an Orwellian-inspired dystopia, this instalment paints a disturbing picture of a subjugated proletariat that produces electricity by pedalling away on exercise bicycles. For their efforts, these humans-turned-generators earn units of a digital currency called “merits”.

The characters dwell in confined, cell-like bedrooms with walls engulfed by LED screens and spend their merits on everyday commodities like food and toothpaste, or to watch particular programs in their quarters. Having inherited millions of merits from his deceased brother, Bing can afford to bypass the advertisements that interrupt these programs.

He meets Abi, a gifted singer, and convinces her to enter Hot Shot, a virtual talent show that rewards its winners with an escape from their enclosed world into a life of luxury and opportunity. The Hot Shot judges, comprised of extravagantly dressed elites of the ruling class, appreciate Abi’s talent, deeming her vocals the finest they’ve heard that season. However, instead of receiving a record deal, Abi is coerced into performing for WraithBabes, a pornography channel, reducing her to an object of sexual gratification.

Later, during, in my mind, the episode’s most distressing scene*, Bing is unable to skip a WraithBabes advertisement that Abi features in, because he spent all of his merits paying for her appearance on Hot Shot. Displayed on screens that track his eye movement, the video follows him around the room as he attempts to divert his attention, and when he closes his eyes, a robotic voice orders him to “resume viewing” in conjunction with a high-pitched screech.

Not only has Bing inadvertently condemned his friend and assumed love interest to a life of sexual exploitation: he is also compelled to watch Abi’s humiliation and mistreatment, at least until he generates enough merits to bypass the WraithBabes pop-up videos.

In this techno-fascist system that converts exercise into the currency required to skip advertisements, thus framing the ability to evade advertising as a luxury attained through labour, advertising itself is depicted as one of the villains, as part of the dominant caste that oppresses the working class of Fifteen Million Merits.

In our world of video streaming and subscription services, the liberty to skip advertisements has also become a purchasable luxury. The cheapest subscriptions to Netflix, BINGE, HBO MAX, Disney Plus, Amazon Prime Video, Paramount Plus, Peacock, and Hulu are all “ad-supported”, meaning the shows and movies you already pay to watch will be routinely interrupted by advertisements. The freedom to look away has become a product available only to those who can pay for it.

For $13.99 a month, YouTube Premium allows you the privilege of an ad-free experience. As of 2025, YouTube also prohibits the use of ad-blocking browser extensions. The advertisements themselves are so jarring that I find myself physically recoiling when presented with one, and I refuse to mitigate this irritation by having the advertiser-free luxury sold to me.

Disengaging with the platform as much as possible thus appears to be the only viable solution. As advertising attempts to colonise every fragment of our attention, the radical act is not to pay for an escape, but to simply stop watching. Unfortunately, in Fifteen Million Merits, Bing is not even afforded that option.

2. Visibility Constitutes Memorability

I’d like to illustrate a complaint that provokes in me a profuse feeling of agitation that, while momentously less harmful than the torment prophesied in Fifteen Million Merits, pertains to the matter of pervasive advertising.

During the Premier League season, which unfolds between August and May annually, I watch the English football on Stan. Sport, the bonus package of an Australian streaming service called Stan. My subscription costs a minimum of $32 per month, which, when scrutinised solely through the lens of monetary value, does not feel too egregious, considering the variety of football available at my fingertips.

In addition to weekly duels in the Men’s division, I have streaming access to the Women’s Super League, domestic cup rounds, European mid-week competitions, FIFA World Cup 2026 qualifying matches, the American Women’s division, and even the Japanese and South Korean domestic competitions.

Because I live in South Australia, being a devoted football supporter requires the surrendering of one’s sleep schedule, as the matches are streamed anywhere between 9PM and 5:30 in the morning. Nevertheless, the timing of these fixtures does not constitute the problem I have with Stan. Sport, as time and football schedules are not at the mercy of my control, and footballers in Europe, Asia, and the Americas cannot be expected to play at a time that befits audiences in every country of the world.

My grievance with Stan. Sport, which subsists microcosmically as a symptom of a far more ubiquitous point of irritation, is the platform’s distasteful and insistent commitment to advertisement, especially the active promotion of itself. Let me offer an example:

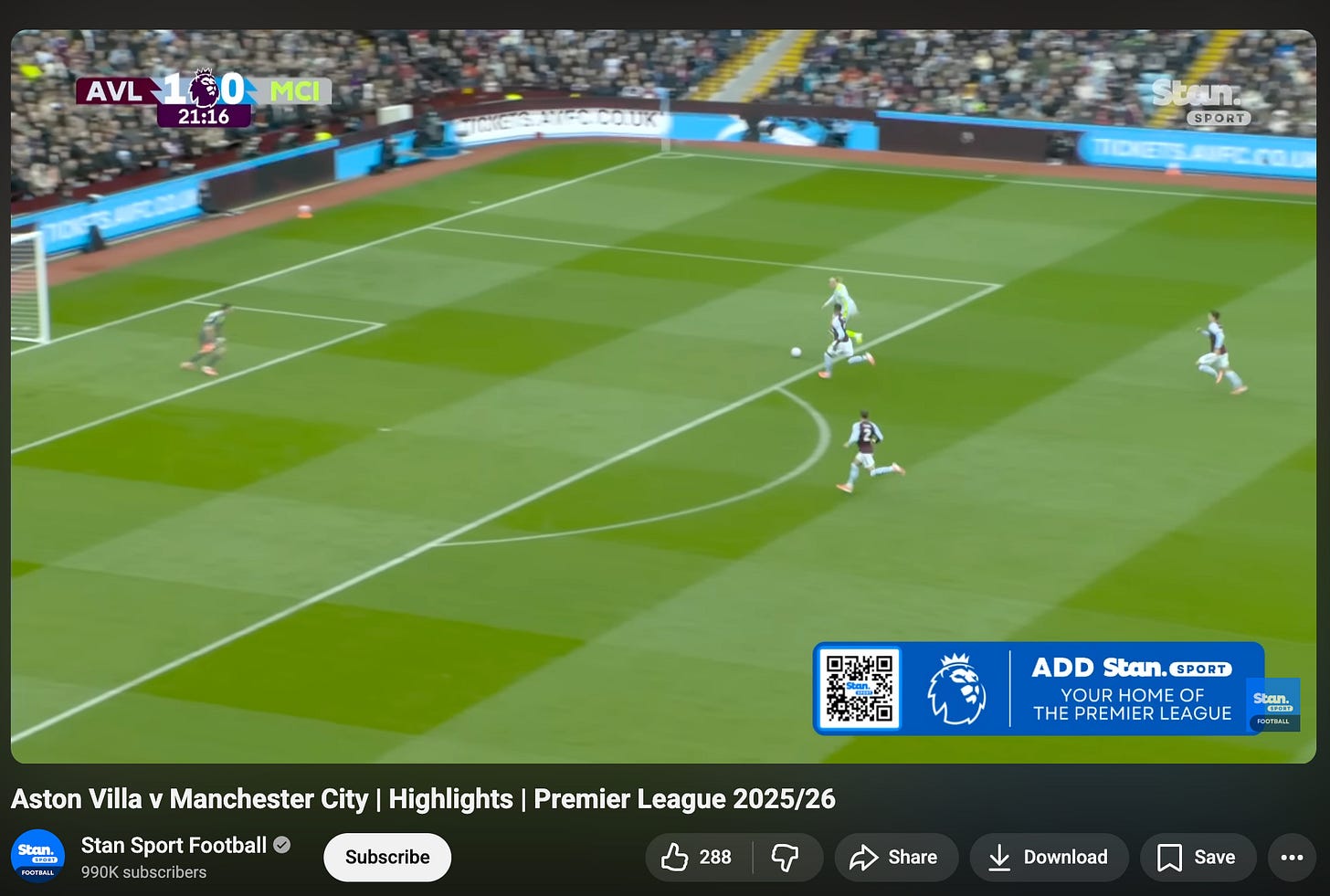

Pictured above is a screenshot from a Stan. Sport’s highlight video on YouTube. Glaringly intrusive in the bottom right corner is an advertisement banner complete with slogan and a QR code that features the company logo within its nucleus, as if it weren’t already identified elsewhere on the screen. This blue eyesore, occupying considerably more space than necessary, does not merely emerge for a moment before promptly disappearing. No, it lingers there for the entire video.

As does the logo in the top right corner, which loiters, albeit in a smaller, less distracting incarnation, for the entirety of these highlight reels and the entirety of every live match. Furthermore, the duration of their highlight videos are routinely contained to two-and-a-half minutes, with the final thirty seconds taken up by, amazingly, another advertisement for Stan. Sport. That’s 20% of the video - time that could be spent showing more of the match’s key events. Have they no shame?

The business, echoing a prevalent contemporary protocol, behaves as though user awareness must be sustained through relentless repetition, that visibility constitutes memorability, that the audience cannot be trusted to distinguish its platform without constant reinforcement.

The reality could not be more different: I am all too aware that I’m watching Stan. Sport, because I pay regular subscription fee to do so. Because, when there’s a football match I want to watch, I search for Stan. Sport on my browser, click on a hyperlink, and have the logo force-fed to me throughout each viewing.

I neither desire nor have any need to be constantly fed advertisements for a service I already pay for because it’s the only platform I can watch the Premier League on without resorting to illegal streaming websites plagued by viruses, scams, crude pop-ups for Temu or pornography, and significant delays, buffers, and interruptions regardless of the strength of your internet connection.

This feels avoidable. I’m paying to watch football, not roll my eyes as I’m smothered by yet more marketing content. Even the half-time intervals are dominated by advertisements, swallowing much of the time that used to be spent on match analysis.

Such a qualm may seem trivial, perhaps nothing greater than a minor annoyance, but as previously stated, this represents a microcosm of advertising’s insidious ubiquity, an infection that has been wilfully evolved within our capitalistic framework to monopolise our eyes and ears, our attention and awareness, as frequently and persistently as possible.

Such pervasive, omnipresent greed has created a bottomless, inescapable cesspool of marketing, with no regard for the human condition, our vulnerability to overstimulation, and our wish to exist as people, rather than faceless, nameless wallets with limbs, valued only for our capital and precious personal data.

3. Dante’s Fourth Circle

In April 2024, my brother and I spent a week in New York City, the financial epicentre of the world’s wealthiest country. Naturally, we visited Times Square, a scintillating complex of sweeping LED displays dubbed Jumbotrons, Spectaculars, and Mega-Spectaculars, parading an unlimited circuit of globalised brands and their celebrity endorsers.

For a minute or two, I genuinely marvelled at this feat of technology, the gargantuan scope, the visual spectacle, the premeditated investment of time, labour and capital to awaken the imagination of so many onlookers. But before long, the novelty wore off, and my eyes acclimated to discern the essence of a phenomenon such as Times Square, that this crude and colourful behemoth of Western consumption really is just one big ad, a cathedral to consumption, Dante’s Fourth Circle of Hell.

Advertising truly has become a universal, all-pervading entity in the Western world, where it now feels impossible to enjoy many activities, whether it be watching a football game or walking through your city, without being overloaded by a tireless crusade of companies petitioning us to invest in their enterprise. Because, as Philip Slater writes in The Pursuit of Loneliness: America’s Discontent and the Search for a New Democratic Ideal”:

“Our economy is based on spending billions to persuade people that happiness is buying things, and then insisting that the only way to have a viable economy is to make things for people to buy so they’ll have jobs and get enough money to buy things.”

The frustrating irony of this condition, however, is that I have little grounds to cast condemnations upon the advertisers alone for engineering this, because widespread advertising fuels the consumerism-driven late-stage capitalism vortex established and perpetuated by the corporations, the elites, the ultra-wealthy, and the unashamedly gluttonous.

For large corporations and advertising agencies, the only extractable assets more valuable than our money are our time and our attention spans. Time equals engagement, and engagement equals profit. Our personal data is mined, harvested, and sold to the highest bidder, all without our knowledge or consent (or both), before ultimately being applied to targeted advertisements for more garbage we have zero need for.

I do not anticipate that the situation we presently find ourselves in will improve. In fact, I can only foresee it growing more egregious as we progress dangerously towards the pleasure-oriented society that Huxley predicted in Brave New World.

4. The Analog Resolution?

Whether through scientific evolution or divine composition, we were not designed to experience the acute levels of visual and auditory stimulation present online. Nor were we designed to have advertisements pressed upon us at every opportunity.

Over coffee with a friend last week, I commented, somewhat facetiously, that the only escape from advertising (in urban life) comes by way of locking yourself in your bedroom and avoiding all technology. Alternatively, I have noticed a growing cultural shift towards the resurgence of “analog”, roused not only by nostalgia and renewed interest in physical media or offline hobbies, but cultivated in revolt against the oversaturated, universal, and exhaustively demanding digital realm.

Rather than a doomsday solution, perhaps we can treat the return to analog, beyond the movement’s other advantages, as a means of avoiding the unwilling consumption of mass advertising.

Because there’s nothing enjoyable about sitting through the streams of unavoidable advertisements that flood the digital world, in which so much of our existence has already become embedded.

*I have not meant to suggest that Bing’s experience in Fifteen Million Merits is somehow more brutal than Abi’s. Being forced to watch ads for your friend’s pornographic videos is obviously horrifying, but being the woman forced into performing in the pornographic videos is unquestionably a far worse fate. Fifteen Million Merits tackles a multitude of distressing subjects - sexual exploitation, body-shaming (with the proletariat being forced to exercise), class divide, and the crookedness of talent shows selling working class people the slim chance to escape poverty - all of which could be discussed at length in an extended review of the episode. However, the intention of this essay was to highlight my grievances with the current state of advertising, hence my focus on Bing’s experience in this case.

Living and writing on the traditional lands of the Kaurna People, I observe that Country is central to the social, cultural, and spiritual lives of Aboriginal people. Sovereignty was never ceded. Always was, always will be Aboriginal Land.

OK, when I got to the point "Times Square as "Dante's Fourth Circle" you totally got my attention. I work in advertising, so I really like the perspective

A skin-crawling and thought provoking read, scattered with your signature ironic humour and an optimistic closing paragraph hoping for the return of analogue media. Great stuff.